TREASURES FROM RURAL JHARKHAND

For international orders, please contact us via WhatsApp on +91-7260815628 or Email at maatikaghar@gmail.com or Chat window

Introduction

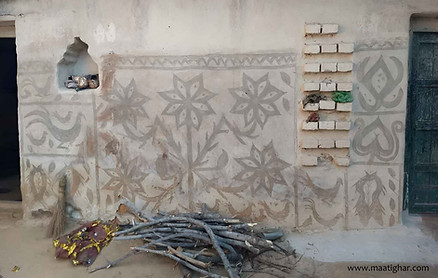

Khovar Painting is a folk/tribal painting tradition that is mostly done in the villages of Jharkhand’s Hazaribagh district. The Khovar art illustrates the socio-religious custom of preparing a wedding room. Traditionally, women of the home paint on the mud walls of houses during weddings to greet and bless the wedded couple.

The paintings are part of a matriarchal tradition in which mothers pass down the art form to their daughters as a legacy. The most common motifs include fertility and fecundity symbols, as well as designs influenced by the environment.

Natural earth colours (white and black) were used in this painting, which were obtained either by foraging in the wild or by purchasing from local stores. Colors are applied with fabric rags on the walls, and motifs are scratched with comb pieces.

Relationship between ISCO rock arts and Sohrai Paintings

Shri Bulu Imam discovered a rock art site in ISCO village of Barkagaon block of Hazaribagh district in 1991 and brought it to light. The rock arts, according to ASI, date from 3000-7000 BC and are from the Paleolithic age. A large number of stone tools have been discovered in close proximity to the rock art site.

Following the discovery of Isco rock arts, a strange resemblance was discovered between the motifs of rock arts and the paintings painted on the walls of local people’s dwellings. They created the paintings on two occasions: one after the rainy season and before the harvest season, and the other during weddings.

Paintings created following the rainy season, specifically around the Hindu festival of Diwali, were known as Sohrai, while those created around nuptials were known as Kohbar.

This suggests that the rock arts of ISCO inspired the paintings of Sohrai and Kohbar, or that the rock arts of ISCO were passed down as a cultural inheritance from ISCO’s occupants to the locals, and then spread throughout Hazaribagh.

‘Khovar’ or ‘Kohbar’ ?

Kohbar is made out of two words: Koh, which means cave, and bar, or var, which means bridegroom. During weddings in the states of Bihar and Jharkhand, a nuptial chamber called Kohvar or Kohbar is decorated with paintings. The artworks’ objective is to greet and bless the wedded couple. Multicolored and black-and-white paintings are both possible.

In Hazaribagh district of Jharkhand, a distinctive style of Kohbar can be seen. These paintings are drawn using the sgraffito technique.

-

A layer of black earth is applied on the mud wall and left to dry.

-

A second layer of white earth is applied over the layer of black earth.

-

Before the white layer dries completely, it is scrapped using comb pieces or fingers to reveal the inner black layer.

Various figures are drawn on the walls using this technique, which takes a high level of talent. Khovar paintings were given this name to distinguish them from other paintings created using same style.

As previously said, Kohvar paintings are usually created during weddings to greet and bless the wedded couple. The bride’s mother and aunts conduct the decorating in this room at the bride’s house.

With their growing popularity, Khovar paintings are now being created alongside Sohrai paintings during the Sohrai festival. The goal is to keep the art form alive and well.

Creation of Khovar Paintings

Who paints Khovar?

Traditionally, Khovar paintings are created by housewives who are married. The indigenous woman is a highly remarkable individual because she is worshipped as Devi, the mother goddess. When she marries, she takes the name Devi, and anything she does is considered a gift from the mother goddess. It is an ancient tradition that only the Devi is allowed to sketch or embroider ritual sacred images linked to marriage and harvest seasons.

The agriculturists, the Ganju and Kurmi, as well as various artisan groups such as the Rana (carpenter), Teli (oil-extractor and –seller), Ghatwar (originally the guards of mountain passes), Prajapati (originally “creators in earth” – clay-modellers), and the Kumhar (potters, workers in clay), practise the Khovar decoration. However, it is particularly unique and prominent among the Oraon, Santal, and Munda ethnic communities in Hazaribagh.

Village women take tremendous satisfaction in their art, which is both a regular element of their home repair and decoration and an inspirational employment and sacred ceremonial tradition that city women lack.

Forms in Khovar paintings

The majority of motifs in Khovar paintings imply auspiciousness, matriarchy, and fertility. Flowers, fish, animals, birds, and abstract symbols associated to marriage, such as Chouk, are the most common motifs in bridal chambers.

The most intriguing part of the Hazaribagh animal and bird forms, as well as the most remarkable quality they exhibit, is the relationships between the forms themselves, as well as the links between the birds and animals and their young, a trait shared by the Indus painted forms. This is a totally matriarchal connection, as evidenced by deer and goats milk-feeding their young or birds feeding their chicks with fishes and insects. A peacock or mongoose fighting with a snake, or snakes fighting amongst themselves, or a mother peacock carrying a small chick on her back, peacocks fighting, or a peahen cracking an egg are all examples of intriguing animal partnerships.

When we descend down into the Barkagaon valley, the village women create much more prosaic, stylised, flowery, and less colourful animal and bird forms, but the art of the hill villages exhibits an exact observation of the wild animals and birds in the heavily forested hill ranges in natural forms.

Current scenario of Khovar art and artisans

Even though these artworks are so important, few people are aware of their existence. These paintings gained international acclaim as a result of Shri Bulu Imam’s international exhibitions, yet they remained unknown in their own country.

Mr. Munna Singh, a CRPF personnel stationed in Hazaribagh, began the paint my city initiative, which helped them gain local popularity. Later, the district government adopted this approach, and these art forms began to be painted on city walls.

When Our Hon’ble Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi visited Hazaribagh to inaugurate the newly built railway station, they gained much-needed national attention. He noticed these murals on the city walls and in the train station. In his weekly radio show, Mann Ki Baat, he discussed these paintings. Since then, these works have gained national notice, with a few practising artists being invited to participate in several art camps.

With this, the paint my city campaign expanded to other cities across the state, and every district was so eager to get Sohrai on their walls that its individuality was lost. Non-traditional Sohrai artists twisted the patterns and colour combinations in most of the areas, according to their understanding, space, time, and most crucially, the money they had.

Such artworks can still be found around the state today. You must visit the villages of Hazaribagh if you want to see the authentic Khovar paintings in their entirety. To see the Sohrai festival, the best time to attend is after Diwali or the day following Diwali. You must act quickly because what was formerly painted by nearly every community in Hazaribagh is now limited to only a handful.

There are two major obstacles in the way of this art form’s survival in its natural habitat. The first is “development,” in which mud huts are replaced by modern concrete houses, and the second is village displacement due to coal mining. Unfortunately, neither will ever come to an end.

There is a pressing desire to comprehend their meaning and appreciate their beauty, which is found in basic motifs rather than sophisticated narrative. Many artists have ceased to practise, and many more are on their way to doing so. Mothers are abandoning the custom of teaching these paintings to their daughters because they find no value in them.

The only way to ensure the survival of this beautiful and vital cultural tradition is to stimulate demand. Individuals, corporations, institutions, and the government all need to lend a hand.

Individuals have the greatest amount of power. We have seen people’s lives change because of the power of individuals in these days of the internet and social media. Khovar art, too, should be treated with respect. These paintings, which are being pushed out of their natural habitats, require new homes to survive, and those homes are ours.

These paintings recently received their Geographical Indication of ‘Sohrai-Khovar Paintings,’ which gives them hope, but hope alone does not conserve traditions; actions do and we must act immediately!

Share this article:

Follow Us on:

Support Artisans, Preserve Tradition

Ready to make a difference? Purchase a Khovar Painting today and support the talented artisans of Jharkhand while preserving their rich cultural heritage. Every purchase empowers these artisans and ensures the continuation of this beautiful tradition for generations to come.